The struggle for an equal status in the job market and the workplace is far from being over…

In an increasingly globalised economy, businesses and governments around the world face the challenge of finding new and unique sources of competitiveness to fuel private sector-led growth. Providing jobs for a growing and increasingly educated workforce require a new development model and approach that rests on capitalising on human resources rather than natural resources.

Although women may constitute nearly half the working-age population worldwide, they represent only one third of the actual labour force and remain a largely untapped pool of human capital depriving families from the potential welfare ensuing from adequate involvement of women in the economy. Progress toward gender equality has stalled during the past decade as women’s participation in the workforce has remained at 50% compared to close on 80% for male participation. The wide gender gap persists in the job market as women still have less opportunities than men to join the job market, still earn less than men, and are much less likely to occupy top managerial positions. The gender pay gap is about 16% in advanced and emerging market member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The participation of women shrinks when it comes to higher managerial positions as fewer than 14% women hold corporate board seats in the European Union, and fewer than 10% of them hold executive positions in Fortune 500 companies. At the regional level, wide variations exist with the Middle East region representing more troubling figures.

Women and work in the Middle East

Much work still needs to be done in terms of economic and educational gender equality in the Middle East despite the commitment shown by the countries of the MENA region to gender equality by signing the Millennium Declaration, with the third goal being ‘to promote gender equality and empower women’.

The average female labour force participation rate across the region is the lowest of any region in the world: 32% of working age women participate in the labour force, compared with 55% in low and middle income countries and 61% in OECD countries.

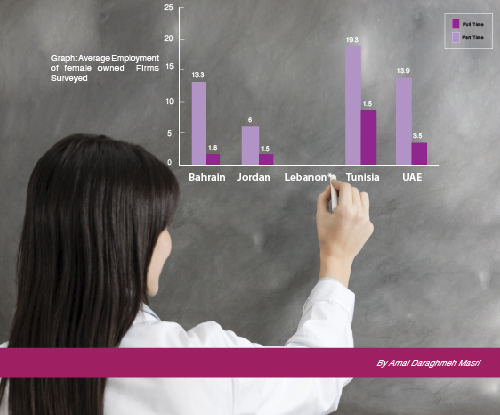

Women’s share of employment in the private sector is generally very low in the Middle East, averaging only 20%, but is below 10% in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Palestine and Yemen. The average rate of self-employment for women across the countries is 10.7% compared to 21.6% for men.

The majority of women are clustered in micro-enterprises with self-employed women less likely to be employers than men: one in four self-employed men is an employer versus just over one in ten self-employed women

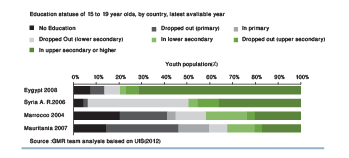

The gender gap in education

These figures are mirrored in the regression in educational attainment in primary and early secondary education in the Middle East region with a gender parity index of 0.93 in primary school and 0.94 in secondary school. In secondary and tertiary education, female enrolment exceeds male enrolment in general. Yet, with an alarming 60% drop out rate in lower secondary education levels, explains the fact why two thirds of the region’s 50 million illiterate population are women. Egypt is amongst the ten countries in the world with over 10 million adults unable to read or write. Furthermore, women workers in this region tend leave the labour force when they marry and have children to a much greater extent than do women in other developing regions.

The wide gender gap in educational attainment leaves a huge skills and qualifications deficit amongst young females with negative implications on higher participation of women in economic activity missing thereby opportunities to improve the welfare of families and society. Higher participation rates were found to increase per capita gross domestic product by an average 0.7 percentage point and family income by as much as 25% when factoring for female education, fertility and age distribution in the region since the beginning of the past decade.

In the Arab States the lack of foundation skills due to failure to complete primary education has placed 10.5 million young people out of the job market, with females being the hardest hit socio-economic strata. Nevertheless, the situation is promising when looking into the remarkable progress achieved in Palestine and Saudi Arabia. As 2015 approaches, Palestine can report favourably on its Millennium Development Goals achievements; enrolment rates at schools reached 97% in 2011 with equal access for boys and girls, the adult literacy rate in the 15-29 age group stood at 94% in the same year. Saudi Arabia which has also made a great advance in women’s literacy in the past decade as 81% of women are literate compared with 57% a decade earlier, and the country is projected to be close to achieving the target of achieving a 50% improvement in adult literacy by 2015. The next decade should witness a noticeable reduction in the number of unemployed youth, particularly females, in these countries.

Actual values that can be derived from education

The marked gender imbalance in educational attainment means that young females of working age lack foundation skills and higher level skills that limit their employment horizons and weakens the impact of their role in the private sector. Each year of secondary schooling increases a girl’s future wages by 10 to 20 %, and increasing the share of girls with secondary education by 1% boosts annual per capita income growth by 0.3%. The extent to which entrepreneurship represents opportunity also varies with educational level as higher education increases the propensity to take risks in business, stimulates innovative ideas, increases responsiveness to different situations, and improves the ability to develop proactive strategies.

Barriers to women’s increased participation

This two-pronged economic and educational gender gap is beset by a set of disabling factors that constrain women’s roles in the economy that are different from those of their male counterparts. Beyond general education, women still lack specific skills including management and leadership skills, financial literacy and technology skills that are critical for businesses and employees.

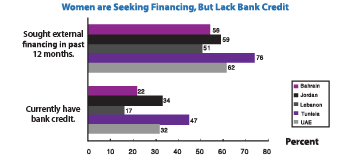

Additionally women also face a further set of additional constraints when it comes to setting-up or expanding a business. Some of these constraints include, weak enforcement of inheritance laws, lack of access to formal credit as many women do not have ownership rights to property, and lack of access to markets, networks or clubs that are dominated by men. Access to credit and capital is a key concern in many countries in the Middle East but only to varying degrees. This issue is ranked as 1st in importance in Jordan, 3rd in Lebanon, 6th in Bahrain but 10th in Tunisia and UAE. Some of the other constraints are similar to those faced by men; high start-up costs, cumbersome and lengthy regulatory requirements, and corruption. In some countries, even a husband’s permission is required to gain employment or enter into contracts!

Once businesses are operating, cultural barriers limit their growth and challenge their daily operations as women have to deal with negative perceptions about their entrepreneurial abilities compared to adult males; they are viewed as having less confidence and experience and less ability than men to start-up and run a business. They are not taken seriously as business owners. Women also have difficulties in networking and building informal business relationships as they are often excluded from male-dominated clubs and networks.

In addition the proven economic benefits in terms of income and GDP that are accrued from increasingly engaging women and helping them join the workforce or start a business, it is important to note that their inclusion brings diversity to a business, which in turn stimulates innovation.

In general, women tend to spend more money on nutrition and the education of their families. Women-led businesses also contribute to economic growth by creating value and providing work opportunities for other women (and men as well). Hence, supporting female business owners and removing barriers that block their participation in economic activity would economically empower them and contribute to improving the welfare of their families. When women and girls earn money, they reinvest 90% of it into their families (versus 30 to 40% for men).

Solutions and recommendations

There are many ways that can help governments tap half of their country’s human resources, talent and ideas. The solution does not simply lie in increasing the economic participation of women, but rather in improving their skills and building on their specific talents to expand their opportunities rather than maintaining the status quo where opportunities for men are created at the expense of women. By increasingly including women in policy-making in the private sector, and in dialogue between the private and public sectors, their different and specific experiences of barriers to economic participation are taken into account which can improve business practices, create solutions and leads to effective policy reforms.

Increasing the participation of women in business associations, enabling them to build capacity and experience to lobby for reforms, and build effective partnerships with stakeholders are all equally important in improving the business climate for women. To help inform policy-makers to make sound decisions, more evidence-based research, gender data and tracking studies need to be developed to capture gender economic activities in both the formal and informal sectors. More importantly, policy-makers need to be persuaded to deal with women’s issues in business as central ones due to the valuable results for businesses and the economy as a whole.

As to persuading society, overcoming negative perceptions about women in business is a serious challenge that requires a progressive change in attitudes that are based on negative stereotypes. An effective communications strategy that promulgates the importance of the role of women in the economy and society is needed. This strategy should be developed by both the private and public sectors, with a fair representation of working women. To encourage married women to stay in their jobs, enter the job market or start a business, the provision of adequate and affordable childcare and more flexible work arrangements are needed.

Finally, incentives to register informal businesses that are owned by women would help recapture economic growth and increase business sector contribution to employment.

Sources: Finance & Development Magazine, June 2013.

Gender and Development in the Middle & North Africa, the World Bank, 2004.

WB World Development Indicators 2011.

The Centre of Arab Women for Training and Research, 2007.

Report of the Palestinian Authority to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee, 2011.

Global Monitoring Report, Education in the Arab States, 2013

FAO Working Paper, The Role of Women in Agriculture, 2011

UNFPA & UNICEF: Women’s and Children’s Rights: Making the Connection, booklet.