The Hajj, How a 1400-year-old holy pilgrimage has become a significant source of income for Saudi Arabia

The Hajj has a deep emotional and spiritual significance for Muslims across the globe. It was in Mecca that the Prophet Mohammad received the first revelations in the early 7th century. The city has long been viewed as a spiritual centre and the very heart of Islam. The rituals involved with Hajj have remained unchanged since its beginning, and it continues to be a powerful religious undertaking which draws Muslims together from all over the world, irrespective of nationality or sect.

In the past, and as late as the early decades of last century, few people were able to “make their way” to Mecca(Makkah) for the pilgrimage. This was because of the hardships encountered, the length of time the journey took and the expense associated with it. Pilgrims coming from the far corners of the Islamic world sometimes dedicated a year or more to the journey, and many perished during it due in part to the lack of facilities en route to Mecca – and also in the city itself.

The circumstances of the Hajj began to improve during the time of King Abdul Aziz Ibn Abdul Rahman Al-Saud, the founder of the modern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Major programmes were introduced to ensure the security and safety of the pilgrims, as well as their well-being and comfort. Steps were also taken to establish facilities and services aimed at improving accommodation, healthcare, sanitation and transportation.

The expense even today of not only travelling to Mecca, but funding accommodation and food (both en route and during the Hajj) can be enormous – not even taking into account the potential cost of gifts offered as acts of devotion and the souvenirs, zamzam water, carpets and beads that are brought back for family and friends.

For some, preparing and saving enough to pay for their trip to Mecca can, in itself, take a lifetime – making it a true journey of devotion. Conversely, for others it can speak volumes about their wealth; being able to take the whole family for a VIP luxury Hajj only happens for the seriously wealthy.

The fact that there is ever increasing business to provide niche services, often providing fully organised guided tours to Saudi Arabia speaks a lot not only about how the world has become a much smaller place (due to air travel). The Hajj provides income for tourist agencies across the globe – it is one event that is sure to occur every year, throughout the year. But how important has this global pilgrimage become to the overall economic performance of Saudi Arabia?

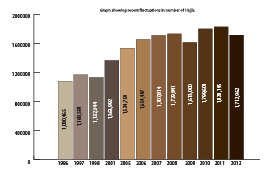

The total number of annual tourists to Mecca and Medina is expected to rise from about 12 million a year to almost 17 million by 2025. Not usually known as a tourist destination due to its very strict rules, especially for women and non-Muslims, it is very unlikely that you would ever visit unless work takes you to the Kingdom, you were visiting for healthcare services … or you were performing the Hajj.

Not only are the hoteliers and shopkeepers making money hand over fist, but so is the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; everything from the airport landing fees, transport tolls, local transportation, taxes and service charges, the money is flowing into the national coffers.

Business reports conclude that Saudi tourism, especially the religious variety, is recession proof. The government’s commission for tourism and antiquities said revenue from tourism in 2010 topped $17.6bn, and is forecast to almost double again by 2015.

The latest efforts to improve the pilgrimage experience by the government, awre of how important religious tourism has become, is the al-Mashaaer al-Mugaddassah metro. The metro is a $6bn, 276-mile rail link that will carry people between Muzdalifah, Mina and Mount Arafat, important locations for pilgrimage rituals. At its peak it will transport 72,000 passengers and go some way to relieving the congestion and frayed nerves experienced every year. Visas for overseas pilgrims to make Hajj were reduced by 20% during the period when redevelopment took place, to avoid overcrowding and to keep pilgrims safe. With a history of deaths due to overcrowding/crushing, this was a sensible decision.

In addition, a $2.4bn upgrade will increase the capacity of Medina airport from 3 million to 12 million passengers a year, and King AbdulAziz International airport (Jeddah) will also expand its capacity, from 30 million travellers (in 2012) to 80 million when finished.

To cater for the wealthier of the pilgrims, a recently developed area in Mecca, Abraj al-Bait, has been created to serve the inevitable urge to shop and stay in quality accommodation during their stay. Abraj al-Bait is a complex of luxury hotels, malls and apartments, has an estimated value of $3bn, a built-up area of 1.4m sq metres, 15,000 housing units and 70,000 sq metres of retail space.

According to a report in Britain’s The Guardian newspaper in 2010, Moroccan, Tunisian, Turkish, British, Algerian and South African pilgrims (Hajjis) like comfort and luxury, whereas Pakistanis don’t patronise high-end hotels. The closer you are to the holy site (less transfer time/walking distance), the more expensive it can be.

The level of pampering offered by some of the hotels – high-end toiletries, 24-hour butler service – may jar with the ethos of sacrifice, simplicity and humility of Hajj but it is not a contradiction felt by the customers snapping up royal suites at $5,880 a night, eating gelato (ice cream) or milling around enormous lobbies of polished marble in their Hajj clothing of bedsheets, towels or burqas.

The view from al-Bait reveals the physical impact of this soaring ambition. All around the Grand Mosque and the Ka’bah, which are overshadowed by cranes and skyscrapers, construction continues at a frenzied pace.

According to those who visit regularly, the mountains of Mecca – Omar, Kaabah, Khandama – will soon no longer exist. The Shamiya district has all but disappeared. From the terrace of al-Bait to street level there is a stench of machine oil and cement that mingles with the more familiar odours of Hajj – sweat, hardship and flipflops.

The Saudi government is publicising how much it values the holy city. Lower-end hotels and local housing are gone, replaced by narrow towers of apartments and high-end hotels. Those that lost their homes in areas marked for redevelopment received compensation and new homes, but this change has meant Mecca is not the place it once was.

Mecca, a place where people from across the globe have travelled to for fourteen centuries, has moved with the times. An event that is one of the globe’s greatest movements of people known to humankind – and one that happens every year without fail – has become an essential part of Saudi’s current and future economic planning, and will probably outlive their national oil reserve.

Sources:

-Saudi Arabia government website, The Guardian newspaper, Gulf News, BBC online, British Museum