Mixed feelings for the latest energy phenomenon:

What the “frack” is Shale Gas?

When news of the discovery of shale gas deposits was announced, excitement and hope for long term revenues for the region followed hard on its heels. But will it be the panacea everyone hopes it will be?

Shale gas is a relatively new source of energy that could solve the global shortage in energy supplies. It promises to offer a sustainable, affordable gas resource that could become one of the most important in future. However, the initial excitement of the news didn’t last long – as with any other new discovery it has its advantages and disadvantages.

What is shale gas and how was it formed?

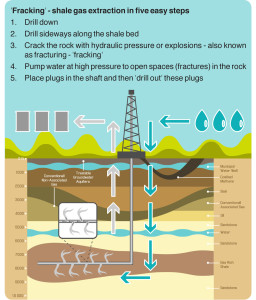

Shale gas is a natural gas characterised by an atypical geologic location, usually found several thousand metres beneath the earth’s surface. It is a fossil fuel from underground shale deposits that are broken up by hydraulic fracturing (at a depth of 1,500m to 3,000m). The process of breaking up the deposits is known as ‘fracking’, which has become somewhat of a controversial subject across the globe in recent years.

French energy firm, Total, provides this précis of the shale gas extraction process: “The origin of shale gas is the same as that of all hydrocarbons – coal, gas and oil. They formed within the source rock, the result of the transformation of sediments rich in organic matter that are deposited at the bottom of oceans and lakes. Over geological time, the sediments gradually became more deeply buried. During this process, they consolidated and sub-surface heat and pressure converted the organic matter they contained into hydrocarbons. Most of the hydrocarbons that formed in this manner were gradually expelled from the source rock and migrated up toward the surface. However, in some cases, their migration was blocked by an impermeable rock barrier”.

Optimistic viewpoint

Estimates from Washington-based World Resources Institute, and as published previously by Bloomberg Business, the supply of clean-burning natural gas would increase by 47% if all the world’s theoretically recoverable shale gas was to be developed. This would lower both greenhouse gas emissions and energy prices.

Shale gas exists in abundant quantities. In North America alone, some experts estimate that somewhere in the region of 1,000 trillion cubic feet of shale gas exists that could supply the United States for more than 50 years.

Shale gas could save some money for consumers as there would be a decrease in energy costs, potentially causing a decline in natural gas prices. As fossil fuels provide the most economical source of power.

It could help countries currently reliant on coal; if they were to extract shale gas, it could provide a cleaner source of energy.

It could provide long-term employment, stimulate economic growth and increase federal/state/local tax revenues.

Secure energy supplies for global users

A report published in June 2013 by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) provided an initial assessment of the globe’s shale oil and gas resources. It assessed 137 shale formations in 41 countries outside the United States, expanding on 69 shale formations within 32 countries.

According to EIA, 32 % of the total estimated global natural gas resources are to be found in shale formations.

The report showed that 345 billion barrels of global shale oil resources and 7,299 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of world shale gas resources are yet to be extracted.

The US possesses 567 Tcf of technically recoverable shale gas. At the 2012 rate of US gas consumption, this represents enough supply for 22 years. In 2011, 34 % of all US natural gas produced was shale gas, and this could rise to 50 % of total US natural gas production by 2040, as projected in the EIA Annual Energy Outlook 2013.

Shale gas resource estimates for some European countries indicate substantial shale gas resources for some countries:

Poland: 12 – 27 Tcf (with potential to rise to 67)

(Polish National Geological Service, March 2012).

Germany: 25 – 81 Tcf

(German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources, May 2012).

UK: 822 – 2281 Tcf

(British Geological Survey, July 2013).

Denmark: 0-13.4 Tcf

(USGS study, December 2013).

Lithuania: 36-181 Tcf

(Lazauskiene & Zdanaviciute, 2014).

This could serve to secure long-term natural gas needs from a domestic source, since currently most European countries rely strongly on imports from places such as Russia which are regularly threatened due to political instability and sanctions.

In Europe, only the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway are natural gas exporters.

Pessimistic viewpoint

Shale gas is connected with significant carbon emissions that are harmful to the environment.

The costs of extracting shale gas are higher compared to those for conventional gas – however, with technological advancements, the costs of drilling and extraction have lowered significantly.

The supply of shale gas is limited because it is non-renewable.

During extraction, large quantities of water are required which could quickly deplete water resources.

Fluids used during the fracking process frequently contain noxious chemicals could accidently contaminate natural aquifers that supply drinking water.

And now for the really bad news: fracking may cause EARTHQUAKES

A report by US news channel NBC explained that the practice of hydraulic fracturing – fracking – involves injecting water, sand and other materials under high pressures into a well to fracture rock. This opens up fissures that allow oil and natural gas flow to be extracted more easily. The process generates wastewater that is often pumped underground into ‘disposal wells’. This resultant wastewater seems to be the cause of a swathe of unexplained earthquakes in a town far from any known seismic zone. Time magazine’s article of May 2014 confirmed recent research into wastewater disposal wells and fracking itself can induce earthquakes. If one undertakes a search via any search engine with the words ‘fracking’ and ‘earthquake’ you will see that there have been numerous incidents globally that have raised the same

Not such a clean green alternative after all?

Natural gas is widely promoted as being one of the cleanest burning fossil fuels. However, it still contributes to the overall damaging effect of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere. A report in 2011 by BBC News’ former environment correspondent, Richard Black, declared that figures announced by the US government and industry indicated that at least a third more methane leaks from shale gas extraction than from conventional extraction – and perhaps more than twice as much. The research, published in Climatic Change journal, stated that; “Compared to coal, the footprint of shale gas is at least 20% greater and perhaps more than twice as great on the 20-year horizon, and is comparable over 100 years”.

In layman’s terms that means that it is as bad, if not worse, than coal for its detrimental affect on the environment.

What about the Middle East and North Africa: Who has shale gas?

Jordan

Jordan has two basins with potential for shale gas and oil, the Hamad (Risha area) and Wadi Sirhan. The target horizon is the organic-rich Silurian-age Batra Shale within the larger Mudawwara Formation.

Morocco

Prospective areas for wet and dry gas of Silurian “Hot Shale” in Moroccan, Mauritanian and Western Saharan portions of the Tindouf Basin have a resource concentration of 19 to 22 billion cubic feet (Bcf). The prospective oil area of the Silurian “Hot Shale” has a resource concentration of 8 million barrels plus associated gas.

Algeria

Algeria’s hydrocarbon basins hold two significant shale gas and shale oil formations, the Silurian Tannezuft Shale and the Devonian Frasnian Shale and the Ghadames (Berkine) and Illizi basins in eastern Algeria; the Timimoun, Ahnet and Mouydir basins in central Algeria; and the Reggane and Tindouf basins in southwestern Algeria.

Tunisia

Tunisia has two significant formations with potential for shale gas and shale oil – the Silurian Tannezuft “Hot Shale” and the Upper Devonian Frasnian Shale. These shale formations are in the Ghadames Basin, located in southern Tunisia. Additional shale gas and oil potential may exist in the Jurassic-Cretaceous and Tertiary petroleum systems in the Pelagian Basin of eastern Tunisia.

Libya

Libya’s has three major hydrocarbon basins: the Ghadames (Berkine) Basin in the west, the Sirte Basin in the center, and the Murzuq Basin in the southwest of the country.

Egypt

Egypt has four basins in the Western desert with potential for shale gas and shale oil – Abu Gharadig, Alamein, Natrun and Shoushan-Matruh. The target is the organic-rich Khatatba Shale, sometimes referred to as the Kabrit Shale or Safa Shale, within the larger Middle Jurassic Khatatba Formation.

Turkey

There are two shale basins in Turkey – the Southeast Anatolia Basin in southern Turkey, and the Thrace Basin in western Turkey. These two basins have active shale oil and gas exploration underway by the Turkish national petroleum company (TPAO) and several international companies. Turkey may also have shale gas resources in the Sivas and Salt Lake basins.

Conclusion

Shale gas will continue to be considered as a controversial energy source. With growing demands from the public for more transparency from those exploiting these reserves, such as EXXON, reports have been created to outline what sort of risks are involved with shale gas production operations, in particular fracking and environmental issues such as wastewater, air pollution, and methane emissions.

However, the main question remains how can we have a renewable sustainable green energy without damaging our planet? Can Arab countries afford any negative effects of the extraction of the shale gas – specifically pollution and the potential damage to aquifers? Do we really need to replace the oil and gas resources we have just yet?